Andrew Moor, my cousin, recently passed away, and I wanted to write a short note to highlight his successful career, focusing on his truly remarkable achievements as the President and CEO of Equitable Bank in Canada.

Our grandparents had four children and 15 grandchildren, and many more great-grandchildren, with just a few of us working in financial services. This note is for Andrew’s family and friends, many of whom do not have financial backgrounds. I hope this will highlight Andrew’s remarkably corporate achievements in relatively simple terms.

Andrew studied mechanical engineering at University College London and went on to do an MBA at the University of British Columbia in Canada, where he settled and raised his family. He spent nearly a decade at Citizens Bancorp, then became the President of SMED, an office furniture business, delivering a successful IPO, followed by a takeover in 2000. He went on to become the President and CEO of Invis, a mortgage company, which he sold to HSBC in 2006, before becoming President and CEO of Equitable Bank (EQB) in 2007.

Most CEOs taking the reins of a bank in 2007, a year ahead of the great financial crisis, would have soon been out of their depth. The IMF estimated total losses in banking during the financial crisis of 2008 to be $4.1 trillion. Yet EQB made a healthy profit that year, and not only that year, but in every single year under his tenure. In his 2008 annual report, he wrote:

“Corporate strength is best measured by the ability to perform over the long term, not just in good times. The record performance Equitable has achieved every year since we became a public company – including 2008 when good economic times gave way to recession – is a powerful indicator of the strength of our business.”

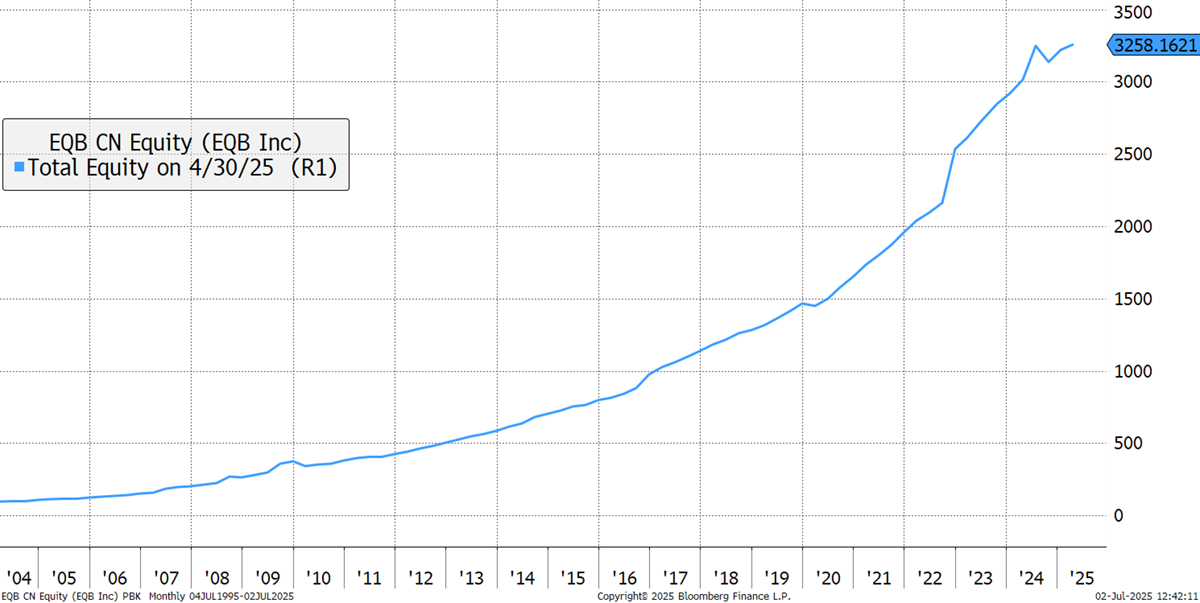

And so it proved. The total equity for EQB in 2007 was C$203 million, which has grown to C$3.14 billion by 2024, an annual growth rate of 18%.

Equitable Bank Total Equity

But Andrew didn’t take the credit in the 2008 annual report, instead attributing the bank’s success to his predecessors since 1970. In 2013, he turned EQB from a trust bank into a schedule I bank (a proper bank). He also stressed the need for the bank to become digital, with “a successful future as a branchless bank built around a digital core.”

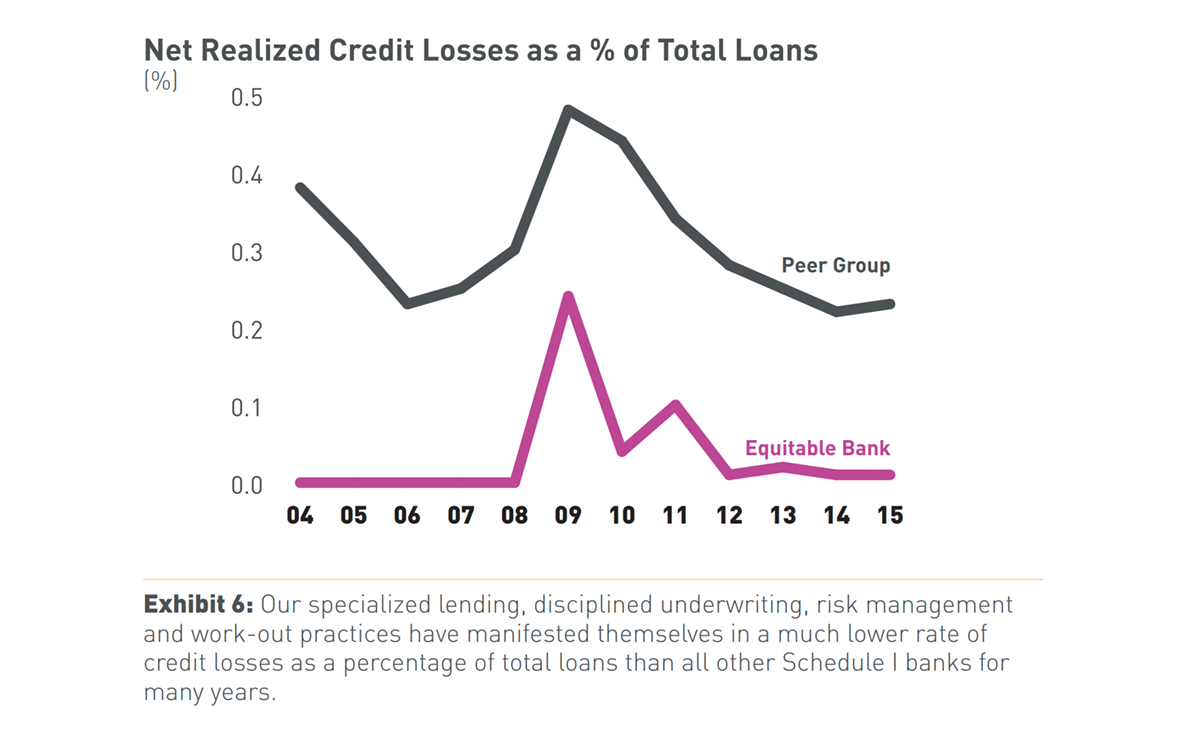

He was heavily focused on having strong capital foundations, and in 2015, highlighted the low default rates among EQB customers compared to the peer group in other Canadian banks.

In 2017, he addressed the threat from fintech (financial technology):

“Much has been written about how fintech and a move to digital banking will make banks themselves obsolete. Some observers expect that the services currently provided by regulated banks will be subsumed by technology giants – think the Bank of Apple – or newer upstarts that are anchored in the provision of cryptocurrencies.

At Equitable, we have no doubt that banking is changing. However, we believe that banks will continue to be central to a reshaped financial services sector. The history of banking’s evolution over millennia would support the view that banks are here to stay. That said, a brief history is in order.

Written language was developed in Mesopotamia in 3,200 BCE. One of the first applications of the new technology of writing was to create banks. The use of cuneiform writing on clay tablets allowed for the creation of organized records of obligations. A system then evolved whereby banks took on the role of being a store of value in society. From these early roots in human civilization, banking has consistently embraced technological change. Notable among these technological advancements was the development of double-entry bookkeeping by the Medici banking empire in the Florence of the Renaissance.

In Canada, banks have always held a central place in society. The country’s oldest bank turns 200 this year. This bank’s founding predates Confederation by 50 years. In those early times, banking was often at the centre of political strife as legislators fought over which entities would be allowed to provide banking services to a growing society. While prominent banks, such as the Bank of Upper Canada, have disappeared into the history books, it is telling that many financial institutions with 19th century roots remain growing concerns today.

The content of Walter Bagehot’s Lombard Street, first published in 1873, seems remarkably familiar to a modern-day banker. Bagehot’s discussion of bank governance issues, liquidity management and sound capital have clear parallels with today’s discussions of governance models, net stable funding ratios and CET1 ratios. The reasons are simple. For banks to stand as institutions that can represent the fundamental trusted store of value in society, these considerations are important and have, and will, endure over time. Even in 1873, Bagehot wrote about the complexity of managing increasing numbers of transactions in the banking world.

Banking services have morphed over time beyond lending and beyond serving as a repository for savings and deposits. Many countries, including Canada, have adopted universal banking models that have banks engaged in a wide variety of activities in many areas of financial services. These business models will be changed and reshaped by technology. Despite rapid technological change however, I am hard pressed to believe we are at an inflection point in history where banking itself becomes obsolete.”

I wonder how many bank CEOs even know who Walter Bagehot is and if they could point to Mesopotamia on a map. Andrew had a wider interest in the history of banking and its important social role in society. He also had a vision for the forthcoming technological revolution.

In going through the annual reports, I couldn’t help but notice how they grew from 64 pages in 2007 to 156 pages by 2023. That demonstrates the weight of regulation that has been imposed upon banks in recent years. Yet it isn’t just regulators, as Andrew joined a relatively small trust bank, valued at C$390 million, which under his tenure grew into a C$4 billion challenger bank with the number of employees growing 12-fold.

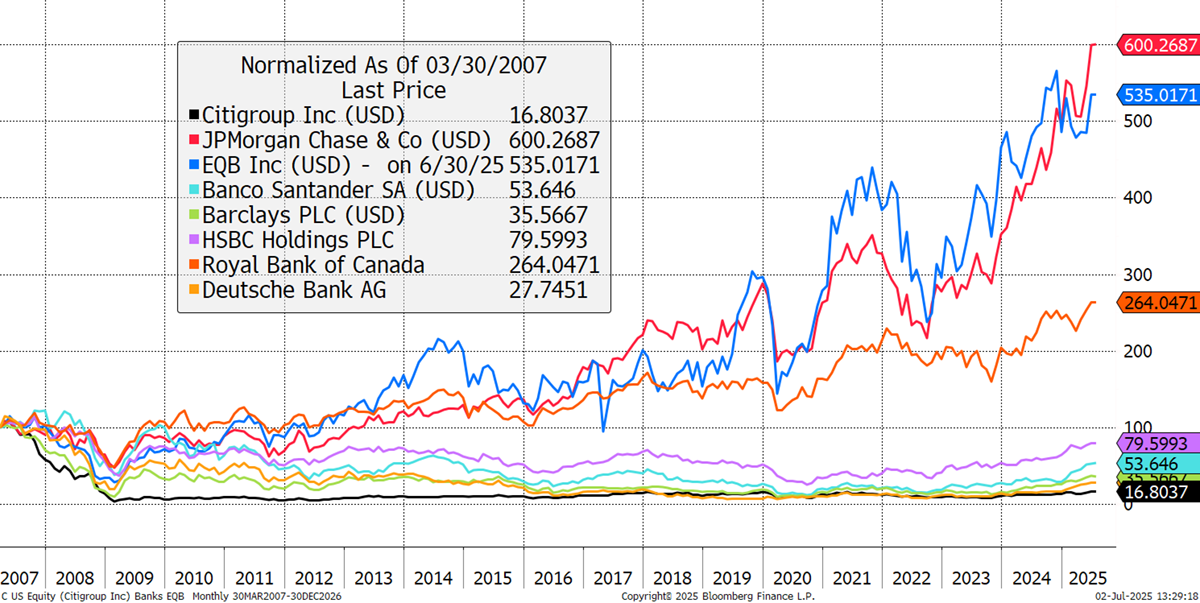

To illustrate the success of EQB against peers, I have plotted the share price of EQB alongside a selection of the world’s largest banks, all starting at US$100 in March 2007. JPMorgan is widely considered to have done a spectacular job during the financial crisis and since. Canada’s RBC isn’t too far behind, but at the bottom are HSBC, Santander, Barclays, Deutsche Bank, and Citigroup, and many other well-known banks. EQB was only narrowly beaten in terms of shareholder returns by JPMorgan during Andrew’s tenure.

Equitable Bank versus Major Banks

I used Bloomberg data to screen all global banks over the period. Since March 2007, EQB has had a total shareholder return, including dividends, of 634% in US dollar terms, which is the 34th out of the 504 banks covered. Only nine of the banks that performed better came from developed countries, with the remainder from higher-growth emerging nations.

In closing, Andrew was an engineer turned businessman, turned banker. He floated a company on the Canadian stockmarket, sold two companies as CEO, and showed the world’s bankers how it’s done. That is not only in financial terms, but with high moral standards, respect for his customers, and compassion for his employees. I want his family and friends to acknowledge his achievements and see the truly staggering job Andrew did as the CEO of EQB.

Andrew Moor, rest in peace.